Some things I dug up while researching my novel Beethoven's Assassins.

Beethoven in Fiction

When was Beethoven born?

What caused his deafness?

Who was the “Immortal Beloved”?

Why "Moonlight" Sonata?

Was Beethoven a Freemason?

What was the "Incident at Teplitz"?

Why "Hammerklavier" Sonata?

Who first played the Hammerklavier Sonata?

Bibliography

Why is Opus 106 called the "Hammerklavier" Sonata?

When I first came to know of this famous sonata – very long ago – I learned two things about it. First, that when Beethoven published it he wanted the title page to be in German and invented a new word to replace pianoforte, so it came out as Grosse Sonate für das Hammerklavier, hence the nickname. Second, that he told his publisher people would still be playing it fifty years later. I always accepted the first story at face value and wondered where the second came from, but it was not until I started researching my novel Beethoven's Assassins that I decided to do some serious digging – and found some surprises. My long-cherished factoids turned out to be in need of correction. So read on – and forgive me if there are a few digressions along the way. The Hammerklavier is a long sonata, so why not have a long introduction to it?

From time to time during his composing career, Beethoven departed from convention and used German rather than Italian tempo indications or French titles. I think the earliest example may be his set of six songs, Opus 75, which he composed in the same year as his piano sonata published as Lebewohl, Abwesenheit und Wiedersehen (Opus 81a).1 That year was 1809, when Austria was defeated by France at Wagram and Napoleon imposed a peace deal that made the countries allies for the next four years, together with other German-speaking territories (at a time when Germany, of course, did not exist as a single nation). When Beethoven resumed his linguistic experiment (with the piano sonata Opus 90) it was following the collapse of that alliance. Napoleon's Russian disaster of 1812 had brought an opportunity to break free: a series of conflicts known as the Wars of Liberation (Befreiungskriege).

1813 saw the formation of the Lützow Freikorps, a patriotic guerilla force of black-uniformed volunteers. One was the poet Theodor Körner, who was planning to write an opera libretto for Beethoven but died in action before completing it. Another was Eleonore Prochaska, who fell in October while fighting in male disguise and was celebrated the following year in a drama for which Beethoven wrote incidental music (Leonore Prohaska, WoO 96). Ludwig Schnorr (an acquaintance of Beethoven) portrayed a costumed woman clutching spears in a painting titled Cäcilia Tschudi as a Valkyrie. According to cultural historian Jost Hermand, "In art historical terms, this work may stand as the earliest known depiction of a Valkyrie in an oil painting. More importantly, however, within the sociopolitical context of the anti-Napoleonic Wars of Liberation this painting represented a longing for liberty, indeed a commendably antifeudal and revolutionary outlook on the part of the young artist.2

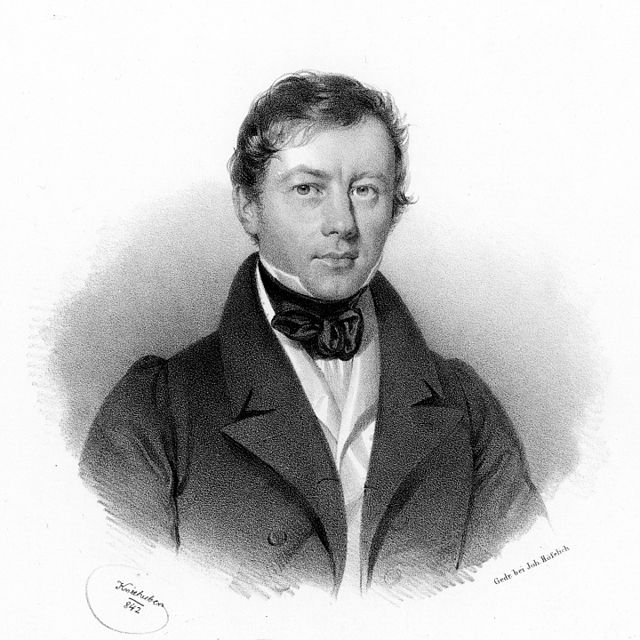

By the start of 1814 Napoleon had been driven out of all German-speaking territories, and in April he signed the treaty ending his rule. On the same day, nineteen-year-old law student Anton Schindler humbly approached Beethoven at a charity concert in Vienna where the Archduke Trio was premiered – their first proper conversation, though it would be some time before they spoke again.3,4 In autumn international diginitaries began arriving for the Congress of Vienna, and Beethoven – who had already gained renewed public popularity with his "Battle Symphony" (Wellingtons Sieg, Opus 91) – produced another celebratory work for the occasion (Der glorreiche Augenblick, Opus 136). Schindler was a player in concerts where these were given, and thus could see Beethoven "at very close range".5 From Schindler's perspective, "This was the unlooked-for beginning of a close relationship. It probably would have gone no further but for a misfortune that soon after befell me."6

Schindler's misfortune was connected with an event at the university that he described as "a riot [Tumult]7 which in itself was insignificant but which neverthless drew the attention of the officials, so that one of the most venerated professors was removed from his post."8 From Schindler's vague account it's impossible to determine when exactly the riot happened; it was either just before he left Vienna in February 1815 to take up a teaching assignment in Brno, or a month or so after his arrival there (judging by a reference to Napoleon's escape from Elba). In any event he was questioned by police in Brno, suspected of involvement with the riot and perhaps of associating with members of the Carbonari, a quasi-masonic revolutionary movement. (More about that here). After a few weeks in prison he was free to return to Vienna to resume his interrupted studies, and it was then that his friendship with Beethoven really began.

According to Erwin Doernberg, "Since young Schindler was a great enthusiast for political reforms, we can be sure that they [he and Beethoven] had much to say to each other. Schindler became the spokesman of a students' society of pro-German tendencies and it was he who drew up the statutes. They included rigorous purism in the use of the German language; anyone using a word of foreign origin had to pay a fine. They even planned to introduce reformed clothes modelled on medieval German attire; but this had to be given up because they found themselves unable to stand up to the ridicule from the non-converted. To what extent Beethoven sympathized with the wilder ideas of the young man remains unknown but we can be certain that anyone in conflict with the political police was eo ipso to his liking."9

It's in this period that Beethoven's interest in German musical terms intensifies. As well as tempo indications (in the piano sonata Opus 90, published in 1815,10 the sonata Opus 101, begun in 1815,11 and the song cycle An die ferne Geliebte, completed April 181612,13) he began considering possible new words for the piano itself. I'm not suggesting that Schindler gave Beethoven the idea of using German for musical terms. Rather I'm arguing that linguistic purism could be seen, at least in some contexts, as an expression of pan-Germanic radicalism.

Writing in October 1816 to Tobias Haslinger (a partner at the firm due to publish Opus 101), Beethoven mentioned having corresponded with Wilhelm Hebenstreit, a writer and editor in Vienna, about "a German equivalent for pianoforte".14 Hebenstreit's letter had been left at the publisher's office and Beethoven wanted it back, asking Haslinger not to show it to anyone. Two German words were already in use, though potentially ambiguous: Klavier (keyboard, also applicable to clavichord or harpsichord) and Flügel (literally "wing", referring to the long case of a harpsichord or grand piano). Beethoven wanted a new German word to use on the title page of Opus 101 - not in case anyone might think the sonata could be played on a harpsichord, but from a desire to have a direct equivalent to pianoforte or fortepiano (which were both in widespread use).

Perhaps Hebenstreit offered more than one possibility, because Beethoven was uncertain what word to adopt. On the autograph manuscript of Opus 101 he wrote "Neue Sonate für Ham-- 1816 im Monat November."15 In January 1817, when Opus 101 was in proof, he wrote to Tobias Haslinger that the inscription should be:16

Sonata

for the Pianoforte

or - - Hämmer-Klavier

composed and

dedicated to

the Baroness Dorothea Ertmann,

née Graumann

by L. v. Beethoven

Beethoven told Haslinger that if the title page had already been engraved he was prepared to pay for a new one, adding, "Hämmer-Klavier is certainly German and in any case it was also a German invention."17 Was Beethoven unaware that the pianoforte was invented in Italy? Or was he perhaps thinking of the more modern (Viennese) type designed by J.A. Stein? And why add the umlaut, making it "hammers-keyboard" rather than "hammer-keyboard"? Perhaps because the word Hammerklavier already existed, and had been applied to various 18th-century keyboard instruments that used a striking action. There had also been types of Bogenklavier with a bowing action (similar to a hurdy gurdy), and even a combined Bogenhammerklavier invented by Karl Greiner in 1779.18 Again, though, there can surely be no possibility that Beethoven thought anyone might attempt to play his music on one of the older instruments.

Other letters to Haslinger at this time show Beethoven's prevarication while Opus 101 was in proof. "In regard to the title, a linguist should be consulted as to whether Hammer or Hämmer-Klavier or, possibly, Hämmerflügel should be inserted."19 Presumably replying to another suggestion from Haslinger, Beethoven wrote, "Tastenflügel ["key-wing"] is a good expression but can only be regarded as a general term for Federflügel ["quill-wing" i.e. harpsichord], Klavier (or Clavichord) etc. Hence I think I can decide on Tasten- und Hammerflügel ["key and hammer wing"]."20 Yet he changed his mind again, and on 23 January 1817 – with typical humour – announced his decision to the senior partner at the firm, S.A. Steiner:21

After a personal examination of the case and after hearing the opinion of our council we are resolved and hereby resolve that from henceforth on all our works, on which the title is German, instead of pianoforte Hammerklavier shall be used. Hence our most excellent L[ietenan]t G[enera]l and his Adjutant and also all others whom it may concern, are to comply with these orders immediately and see that they are carried out.

Instead of Pianoforte

Hammerklavier –

This is to be clearly understood once and for all –

issued etc., etc.,

by the G[eneralissim]o

on January 23, 1817.

Beethoven's insistence on German for the title page of Opus 101 went even further. The sonata was due to appear in February 1817 as the first number of Steiner's new series, Musée musical des clavicinistes [sic]. Beethoven instructed that this should instead be written in German, with French underneath.22 In fact Steiner printed it the other way round, and was also free with Beethoven's other orders, the sonata being billed both as pour le Piano-Forte and für das Hammer-Klavier (the double-m being printed as a single m with macron).

A few weeks later, the Wiener Moden Zeitung23 mentioned a virtuoso performance by Hieronymous Payer on the "Fortepiano (Hammerklavier)". Had Beethoven's sonata started a trend? I don't think so. The paper's editor was Wilhelm Hebenstreit, the person whom Beethoven had consulted. Hebenstreit presumably wrote the article, and was promoting the word he'd coined and hoped would become standard – though it was destined never to catch on, except as nickname for Beethoven's next sonata.

That sonata – the one we know as the Hammerklavier – was begun some time between autumn 1817 and spring 1818.24 Schindler had graduated by this time and was working as a law office clerk; he claimed that already he had become "Beethoven's private secretary – without pay"25 though Thayer judged Schindler's "factotum" role to have been later and shorter (1823-5).26 Schindler was no longer involved in student politics, but events elsewhere are worth mentioning for the light they shed on the developing situation.

October 1817 marked the fourth anniversary of the Battle of Leipzig and the tricentenary of Luther's Ninety-five Theses, and there were many celebrations of these totems of German pride. One was a two-day student festival near Wartburg Castle in Thuringia, and the organisers made sure it expressed their goals. "First, they adopted the black, red and gold flag of the Lützow volunteer corps, styling themselves as a continuation of these soldiers in an ongoing 'holy war' for the German nation. Second, festival-goers published a statement of principles at the very site where Luther had undertaken his translation of the New Testament."27 These principles included, "political and economic unity for the 'German nation'; a constitutional monarchy with parliamentary representation; equal protection under the law; and the guarantee of freedoms of the press and speech."28

The festival was peaceful and unremarkable, but is remembered for what happened at the end, after all but a few dozen attenders had left, when nineteen-year old Hans Ferdinand Massmann brought what appeared to be a basket of books to one of the bonfires. He gave a speech denouncing each book in turn, asking if it should be thrown onto the flames, and his five inebriated associates called "yes" to every one. The few dozen bemused onlookers didn't realise it, but what they actually saw incinerated at the "Wartburg book-burning" were bundles of paper "torn from dictionaries and romance novels".29 The police investigated, there were rumours of large-scale conspiracy, and it led to a clampdown on student fraternities. A final straw came in March 1819 when a student who had been present at the festival murdered a writer who had been symbolically burned, August von Kotzebue (author of The Ruins of Athens, for which Beethoven wrote music). It was the pretext for harsh new laws (the Carlsbad Decrees) that turned Austria into a virtual police state and kept it that way until well after Beethoven's death.

Beethoven may have completed the Hammerklavier sonata in the autumn of 1818,30 though it didn't find a publisher until the following year. Beethoven first tried to sell it in England with the help of Ferdinand Ries who had settled there. Beethoven sent Ries a copyist's manuscript, and wrote in March 1819, "Should the sonata not be suitable for London, I could send another one; or you could also omit the Largo and begin straight away with the Fugue which is the last movement; or you could use the first movement and then the Adagio, and then for the third movement the Scherzo – and omit entirely no. 4 with the Largo and Allegro risoluto. Or you could take just the first movement and the Scherzo and let them form the whole sonata."31 This astonishing disregard for the integrity of his own work indicates desperation – he was in need of cash. Beethoven sent Ries numerous corrections and addenda, including a famous late stroke of genius - the first bar of the Adagio. Beethoven also sent metronome markings for the sonata, which would – in theory – make traditional tempo indications superfluous. Yet he retained those, reverting to Italian. As for the metronome markings, they are notoriously fast, and have been a subject of debate ever since.

Beethoven's closest associate at this time was not Schindler but Franz Oliva (more about him here), and it is from this period that we have the earliest surviving "conversation books", used whenever words had to be written down for Beethoven to understand them. On 28 April 1819 we find Oliva advising Beethoven on his summer travel and accommodation arrangements, financial affairs, and the guardianship proceedings over nephew Karl. Oliva also writes, "I shall speak with Artaria about it, so that they publish the work in the most beautiful manner, because that way most is done for it. Ries, however, deals directly with the music dealers in London himself. Write to Ries; I shall take care of the rest in sending the letter through business channels, whatever is best."32 Oliva's dealings with Artaria over the Hammerklavier Sonata may be why there is so little about the negotiations in Beethoven's correspondence.

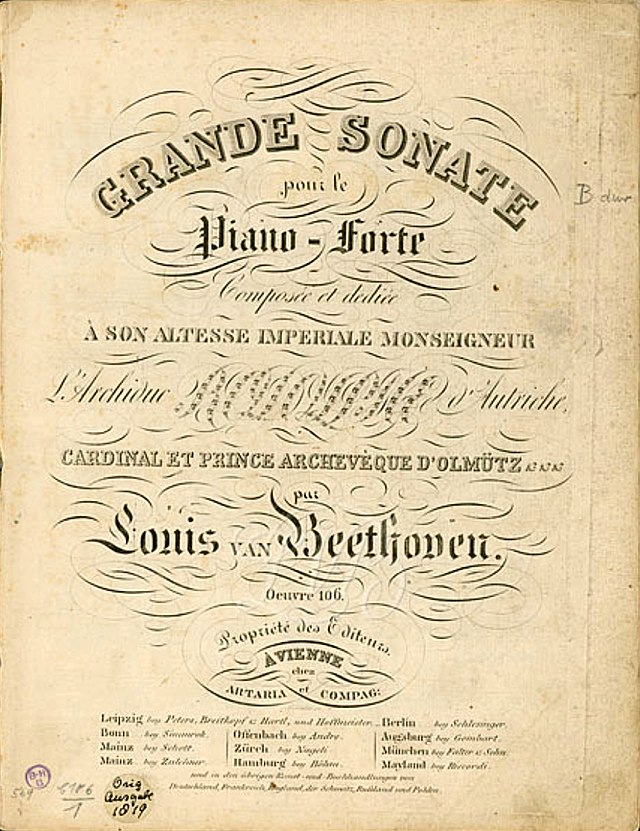

In August the sonata was in proof, and Beethoven wrote to Artaria, "The title is good and can be sent to Guttenbrun [in Romania], to Othaheite [Tahiti], Calcutta, Pondicheri and, what is more, to Greenland and North America. But you must write Grosze instead of Grosse, for the latter is an Austr[ian] provincialism."33 We can suppose that he wanted the German title Grosze Sonate für das Hammerklavier. But when Artaria published the sonata the following month, the title page read: Grande Sonate pour le Piano-Forte... par Louis van Beethoven. Beethoven's next sonata, Opus 109, was published by Schlesinger in November 1821, and Beethoven again requested Hammerklavier,34 though it was printed as Sonate für das Pianoforte. For his remaining piano works he was content with traditional nomenclature. His only composition whose first edition bore the word Hammerklavier (or Hammer-Klavier) was Opus 101. (But see further remarks here.)

Why was Beethoven's enthusiasm for German tempo indications so spasmodic? Did his fluctuating desire for linguistic purity reflect the changing political climate? Or was he swayed by realisation that in the international market he craved, it was better to stick to words everyone knew? In any event, when Artaria issued a new edition of Opus 106 in 1823 it was under the title Grosse Sonata für das Hammer-Klavier,35 and the piece became commonly known by that name.

Now what about that other factoid I learned in my youth – Beethoven's claim to his publisher that the sonata would still be played fifty years hence? To us it sounds terribly modest, though at the time it would have been quite a boast. Where does it come from? Certainly not Schindler or Thayer, nor do we find it in Beethoven's correspondence or Conversation Books. Taking a guess at Wilhelm Lenz (the man who put the Moonlight Sonata on Lake Lucerne – as told here) I found the quote in a Beethoven book Lenz published in 1860: "Da haben Sie eine Sonate, die den Pianisten zu schaffen machen wird, die man in 50 Jahren spielen wird." ("There you have a sonata that will tax the pianists and will be played in 50 years.")36 Lenz cited an 1853 article by the French-Polish pianist H.L.S. Mortier de Fontaine (1816-1883), who said he'd heard it from the publisher Artaria. Since the members of the Artaria family whom Beethoven dealt with were dead by the 1830s, we can guess that Mortier de Fontaine heard it from someone at the publishing company who heard it from someone who knew Beethoven. Or someone made it up.

Addendum. Nottebohm said the sonata first appeared in September 1819 as Artaria's publication number 2588 with the title, "Grosse Sonata für das Hammer-Klavier", together with a catalogue of works from Opus 1 to Opus 106.37 This was incorrect. The story of first publication is complicated, and was discussed at length by Kinsky and Halm.38 Artaria wanted to publish the sonata together with a catalogue of Beethoven's works, and asked him to supply information, but he was too busy, so the sonata was initially published without that catalogue, which was added to a later edition. According to Kinsky-Halm, the sonata was at first simultaneously published in two versions, one with a French title page and one with German (but both without the catalogue). Kinsky-Halm rejected the earlier opinion of Theodor Steingräber, who had researched the matter in the 1870s and had reached the conclusion that the first edition was the French one, followed "around 1823" by a German-titled edition that included the catalogue. Kinsky-Halm based their dual-edition theory on surviving correspondence and other circumstantial evidence; for instance that in September 1819 Artaria advertised the work in the Wiener Zeitung with the German title. Also they accepted Nottebohm's report that the only copy he'd found in Archduke Rudolph's music collection was of a German edition without the opus catalogue. But are there any surviving copies of this alleged German version of the first edition? I don't know - the Beethoven-Haus Bonn has two items it describes as Originalausgabe (original edition), and both have the French title page. Their collection also includes several copies with the German title page, all described as Titelauflage (reissue). So in summary, the question of first publication is about as fraught as that of first performance. The Hammerklavier Sonata certainly appeared in September 1819 with a French title page. It possibly appeared at the same time with a German one, if the Kinsky-Halm theory is correct. A first edition was auctioned at Sotheby's in 2011, and another in 2020 - both bearing the French title page. A bound collection of "first and early editions" auctioned in 2018 included the German-titled version with opus catalogue.

References

1. Thayer-Forbes, p521

2. Heroes, p1

3. Schindler-MacArdle, p203

4. Thayer-Forbes, p578

5. Schindler-MacArdle, p203

6. Schindler-MacArdle, p203

7. Schindler-Kalischer, p277

8. Schindler-MacArdle, p203

9. Doernberg, p373

10. Thayer-Forbes, p631

11. Thayer-Forbes, p659

12. Thayer-Forbes, p659

13. Anderson, p572

14. Anderson, p608

15. Anderson, p660 n2

16. Anderson, p657

17. Anderson, p657

18. Riemann, p55

19. Anderson, p660

20. Anderson, p661

21. Anderson, p654

22. Anderson, p659

23. WMZ, 15 March 1817, p187

24. Thayer-Forbes, p681

25. Schindler-MacArdle, p204

26. Thayer-Forbes, pp821, 942

27. Press, p622

28. Press, p622

29. Press, p625

30. Schindler-MacArdle, p228

31. Anderson, pp804-5

32. Conversation Books, Vol 1, p45

33. Anderson, p832

34. Anderson, p916

35. LZ, 4 February 1823, p254

36. Lenz 3, Part 4, p32

37. Nottebohm TV, p101

38. Kinsky-Halm, pp292-6