Some things I dug up while researching my novel Beethoven's Assassins.

Beethoven in Fiction

When was Beethoven born?

What caused his deafness?

Who was the “Immortal Beloved”?

Why "Moonlight" Sonata?

Was Beethoven a Freemason?

What was the "Incident at Teplitz"?

Why "Hammerklavier" Sonata?

Who first played the Hammerklavier Sonata?

Bibliography

What was the "Incident at Teplitz"?

Something happened when Beethoven met Goethe at Teplitz in 1812. Here's how it was described by their mutual friend Bettina von Arnim:1,2,3

While they were walking there came towards them the whole court, the Empress and the Dukes; Beethoven said: “Keep hold of my arm, they must make room for us, not we for them.” Goethe was of a different opinion, and the situation became awkward for him; he let go of Beethoven’s arm and took a stand at the side with his hat off, while Beethoven with folded arms walked right through the dukes and only tilted his hat slightly while the dukes stepped aside to make room for him, and all greeted him pleasantly; on the other side he stopped and waited for Goethe, who had permitted the company to pass by him where he stood with bowed head. “Well,” he said, “I’ve waited for you because I honor and respect you as you deserve, but you did those yonder too much honor.” Afterwards Beethoven came running to us and told us everything and was glad like a child because he had so teased Goethe.

Note that Bettina von Arnim wasn't actually there to witness the incident, but said she heard it from Beethoven. Also significant is the time that passed before she mentioned it to anyone. Her undated letter (to her friend Hermann Pückler) was probably written in 1832, around the time of Goethe's death, and five years after Beethoven's. It only became public in the 1870s, after sender and recipient were themselves dead.4 Had she really remembered the event exactly as Beethoven described it? Had she embroidered the details? The alleged incident remains famous – but rests on shaky grounds.

Bettina von Arnim conducted an extensive, mildly flirtatious correspondence with Pückler (sometimes signing herself "your tame tiger"5), similar to her previous idolatrous relations with Beethoven and Goethe. In 1835, with Pückler's encouragement, she published Goethes Briefwechsel mit einem Kinde ("Goethe's Correspondence With A Child"), she being the "child", and Pückler the book's dedicatee. Supposedly a memoir drawing on actual letters and conversations, it now appears to have involved a good deal of poetic licence, to the extent that some modern critics consider it a novel. Whatever its status as fact, it brought her instant fame, and to the reading public she became known simply as Bettina.

The book included conversations she supposedly had with Beethoven, and comments by Goethe to her about the composer. But while Bettina took credit for bringing about the meeting at Teplitz, her book made no mention of what took place. Then in the autumn of 1838 she was visited in Berlin by Julius Merz, editor of a Nuremberg magazine, and Bettina gave him some handwritten letters, telling him, "There is something for the Athenaeum".6 They were published as lead article in the January 1839 Athenaeum für Wissenschaft, Kunst und Leben, under the title "Three Letters from Beethoven to Bettina". She also gave copies to music critic Henry Chorley, allowing them to be translated and published in Ignaz Moscheles' English version of Schindler's Beethoven biography.7 The third letter, headed "Teplitz 1812", is what first made the incident with Goethe publicly known, and remains the most famous account. Here it is, as published by Moscheles in 1841:8

Dearest, good Bettine [sic],

Kings and princes can indeed create professors and privy councillors, and bedeck them with titles and orders; but they cannot make great men—spirits that rise above the world's rubbish—these they must not attempt to create; and therefore must these be held in honour. When two such come together as I and Göthe [sic], these great lords must note what it is that passes for greatness with such as we. Yesterday, as we were returning homewards, we met the whole Imperial family; we saw them coming at some distance, whereupon Göthe disengaged himself from my arm, in order that he might stand aside; in spite of all I could say, I could not bring him a step forwards. I crushed my hat more furiously on my head, buttoned up my top coat, and walked with my arms folded behind me, right through the thickest of the crowd. Princes and officials made a lane for me: Archduke Rudolph took off his hat, the Empress saluted me the first:—these great people know me! It was the greatest fun in the world to me, to see the procession file past Göthe. He stood aside, with his hat off, bending his head down as low as possible. For this I afterwards called him over the coals properly and without mercy, and brought up against him all his sins, especially those against you, dearest Bettine! We had just been speaking of you. Good God! could I have lived with you for so long a time as he did, believe me I should have produced far, far more great works than I have! A musician is also a poet; a pair of eyes more suddenly transport him too into a fairer world, where mighty spirits meet and play with him, and give him weighty tasks to fulfil. What a variety of things came into my imagination when I first became acquainted with you, during that delicious May-shower in the Usser Observatory, and which to me also was a fertilising one! The most delightful themes stole from your image into my heart, and they shall survive and still delight the world long after Beethoven has ceased to direct. If God bestows on me a year or two more of life. I must again see you, dearest, dear Bettine, for the voice within me, which always will be obeyed, says that I must. Love can exist between mind and mind, and I shall now be a wooer of yours. Your praise is dearer to me than all other in this world. I expressed to Göthe my opinion as to the manner in which praise affects those like us; and that by those that resemble us we desire to be heard with understanding; emotion belongs to women only (pardon me for saying it!): the effect of music on a man should be to strike fire from his soul. Oh, my dearest girl, how long have I known that we are of one mind in all things! the only good is to have near us some fair, pure spirit, which we can at all times rely upon, and before which no concealment is needed. He who will SEEM to be somewhat must really be what he would seem. The world must acknowledge him—it is not for ever unjust; although this concerns me in nowise, for I have a higher aim than this. I hope to find at Vienna a letter from you; write to me soon, very soon, and very fully. I shall be there in a week from hence. The court departs to-morrow; there is another performance to-day. The Empress has thoroughly learned her part; the Archduke and the Emperor wished me to perform again some of my own music. I refused them both; they have both fallen in love with Chinese porcelain. This is a case for compassion only, as reason has lost its control; but I will not be piper to such absurd dancing—I will not be comrade in such absurd performances with the fine folks, who are ever sinning in that fashion. Adieu! adieu! dearest; your last letter lay all night on my heart and refreshed me. Musicians take all sorts of liberties! Good Heaven! how I love you!

Your truest friend, and deaf brother,

BEETHOVEN.

Another of Bettina's friends was Philipp von Nathusius, and her correspondence with him is presumed to have been the source for a book she published in 1848. Like her earlier Goethe book, it can be considered either as memoir or novel, the correspondents in this case being given the names Pamphilius and Ambrosia. Some of their talk is about Beethoven, and Ambrosia says she will send Pamphilius three letters she once received from the composer – not copies but originals, for Pamphilius' autograph collection.9 The three letters reproduced in the book are the same that were published in 1839, with only minor changes attributable to editorial interventions. The third letter now had as footer, "Teplitz, 15th August 1812".10

The only source we have for the incident at Teplitz is that letter (in its two published versions), and Bettina's 1832 letter to Pückler. Neither Goethe nor Beethoven – nor any of the courtiers supposedly present – ever said anything about Beethoven barging through the Imperial entourage instead of bowing. Yet Schindler accepted the story as true, and so did A.W. Thayer, who had meetings with Bettina in 1849-50 while researching his Beethoven biography.11 But before Thayer could complete his work, doubt was expressed by A.B. Marx in a biography published shortly after Bettina's death in 1859. Marx thought the Teplitz letter must at the very least have been heavily reworked by Bettina, if not completely invented. The character it expressed, he said, was not so much Beethoven's as hers, reflected within her own "confused mirror frame".12

Thayer was enraged at this attack on someone no longer able to defend herself, and in 1863 sent word to Julius Merz, who had first published the "Three Letters from Beethoven to Bettina" in 1839. Could Merz confirm that he had seen the originals in Beethoven's own hand? Merz could not, and none have ever been found. It was only after Bettina's letter to Pückler was published in 1873 that Thayer finally saw a "crushing argument against the authenticity" of the Teplitz letter.13 Remember that Bettina said Beethoven had told her about the incident immediately after it happened. So why would he then have written her a long letter describing it? To this can be added two further problems: Beethoven wasn't in Teplitz in August 1812 (he left at the end of July), and Archduke Rudolph wasn't there at all that summer.14 The Teplitz letter was a hoax.

Of course that doesn't mean the incident never happened. But if it did, why did Bettina wait so long to mention it, and why in the way she did? And why had no one else ever spoken of it? The greatest likelihood is that Bettina made it up.

Bettina was thoroughly Romantic in her outlook. What she presented in her writing was "truth" as she saw it – not necessarily objective facts, but a subjective reality. Her Beethoven letters (all three of which must be considered suspect) express the composer as she saw him, as we continue to see him, and perhaps as he saw himself. Lines from them are still widely quoted under the assumption that Beethoven really said them. So too are remarks that Bettina attributed to Beethoven in her Goethe book.

According to Bettina,15 Beethoven said that "music is a higher revelation than all wisdom and philosophy",16 "the mediator between intellectual and sensuous life",17 "the one incorporeal entrance into the higher world of knowledge which comprehends mankind but which mankind cannot comprehend."18 J.W.N. Sullivan quoted these remarks in Beethoven: His Spiritual Development, fully aware that Bettina "was not a perfectly truthful person",19 yet convinced they genuinely expressed Beethoven's views, if not his exact words. "We may assume," Sullivan wrote, "as the irreducible minimum basis of [Bettina's] fantasies, that Beethoven regarded art as a way of communicating knowledge about reality."20 We could equally suppose that the view of art being expressed was Bettina's own, projected onto Beethoven. Aphorisms always seem more profound when attributed to great sources.

Bettina von Arnim made the world see Beethoven as she saw him, and as she wanted him to be seen. She invented the incident at Teplitz, and made the world believe it. She was a novelist, good at making things up. We should admire her for that – but not confuse fiction with fact.

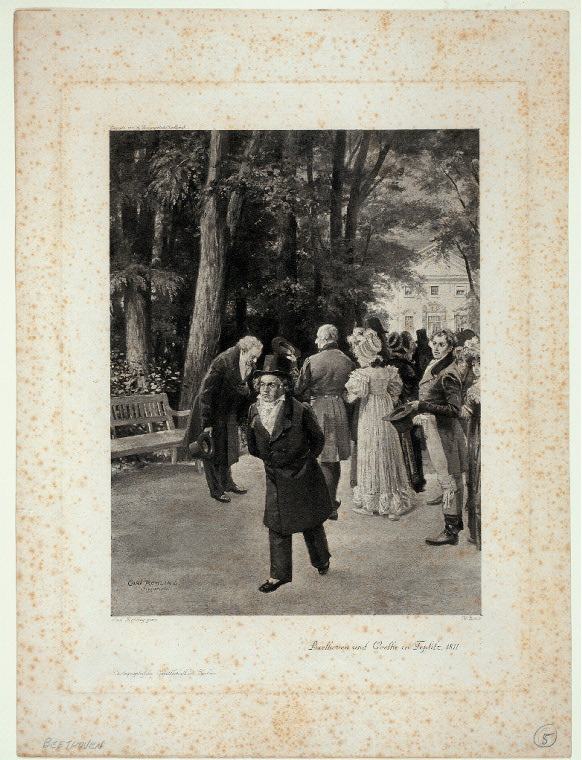

New York Public Library Digital Collections; Photographische Gesellschaft © 1901

The picture that numerous websites refer to as "The Incident at Teplitz" was originally called Beethoven und Goethe in Teplitz, 1811 (an incorrect date for the non-existent event); and since the artist Carl Röhling was a prolific book illustrator I guess the picture was originally made for that purpose, though I haven't been able to identify the book in question. On 17 October 1937, at what was then called Teplice-Šanov or Teplitz-Schönau, some members of the pro-Nazi Sudeten German Party claimed mistreatment by Czech police (possibly falsely), in what was described as the "incident at Teplitz" (e.g. in the Manchester Guardian, 23 Oct 1937, p17) or "the incident at Teplitz-Schönau". The title "The Incident at Teplitz" seems to have attached itself to Röhling's picture only in the internet era, along with the supposed creation date of 1887, which I haven't been able to verify. Like the fictitious incident it depicts, the picture has taken on a pseudo-reality all of its own.

References

1. Thayer-Krehbiel II, p227

2. Sonneck, p84

3. Pückler-Muskau, p94

4. Pückler-Muskau, pp90-94

5. Pückler-Muskau, p253

6. Thayer-Krehbiel II, p185

7. Schindler-Moscheles, Vol I, pp265-274

8. Schindler-Moscheles, Vol I, pp271-274

9. Arnim 2, Vol II, p205

10. Arnim 2, Vol II, p220

11. Thayer-Krehbiel II, p181

12. Marx, Vol II, p134

13. Thayer-Krehbiel II, p227

14. Schindler-MacArdle, p515

15. Arnim 1, Vol II, pp190-200

16. Thayer-Forbes, p494

17. Thayer-Forbes, p495

18. Thayer-Forbes, p496

19. Sullivan, p4

20. Sullivan, p5