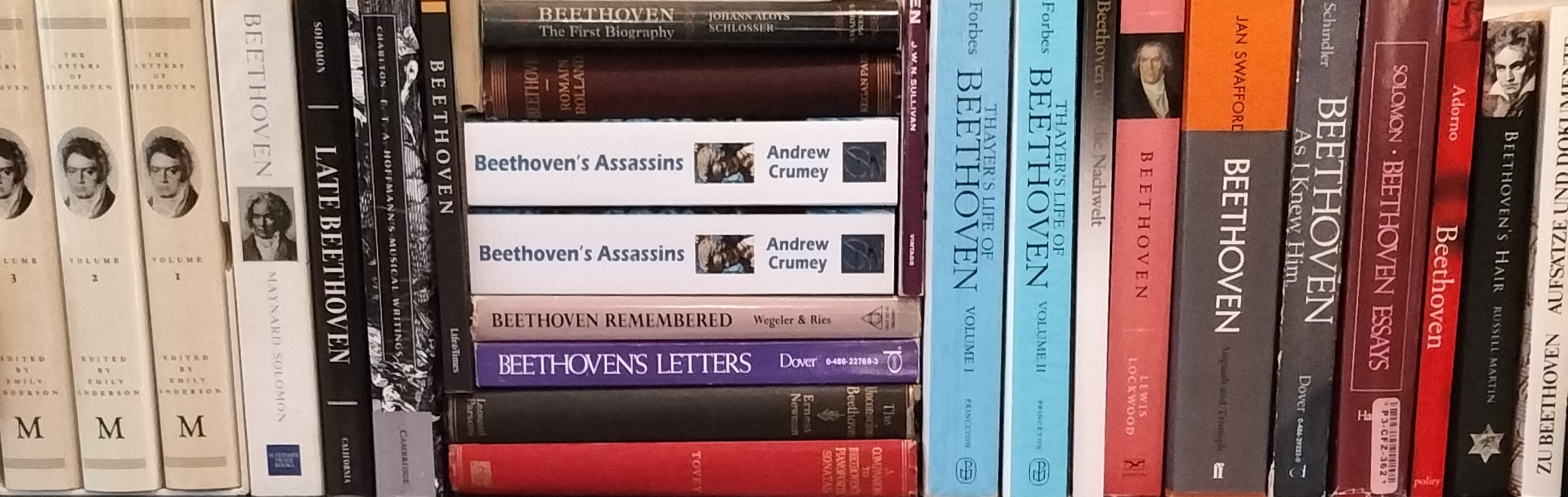

Some things I dug up while researching my novel Beethoven's Assassins.

Beethoven in Fiction

When was Beethoven born?

What caused his deafness?

Who was the “Immortal Beloved”?

Why "Moonlight" Sonata?

Was Beethoven a Freemason?

What was the "Incident at Teplitz"?

Why "Hammerklavier" Sonata?

Who first played the Hammerklavier Sonata?

Bibliography

I knew when I began writing Beethoven's Assassins that there were already a great many novels featuring him. But who first turned Beethoven into fiction, and when?

Stories about Beethoven appeared during his lifetime – presented as fact. For instance it was said that as a boy, practising violin, he noticed a spider sitting on the instrument, and "When his mother discovered her son's companion, she killed it, whereupon the boy smashed his violin to bits."1. The story actually originated around 1800, about a French musician called Berthaume, then became attached to Beethoven, for example in an article printed in 1827.2 There were also rumours about Beethoven's parentage: in 1810 the Dictionnaire historique des musiciens reported: "Louis van Beethoven, said to be the natural son of Friedrich Wilhelm II, King of Prussia, was born at Bonn in 1772."3 This was reprinted in a German book that went through multiple editions, to the horror of Beethoven's friends, though he was slow to seek a correction to the suggestion of illegitimacy, and 1772 was the year he thought to be correct for most of his life (more about that here).

Beethoven was mentioned in various literary works during his lifetime. A notable example is Ludwig Rellstab's Theodor (1824), believed to be the origin of the Moonlight Sonata's nickname (more about that here), though it's not certain if Beethoven was ever aware of it. Beethoven did know about E.T.A. Hoffmann's story collection Fantasiestücke in Callots Manier, having been told in 1820 via conversation book that he, Beethoven, was "very much the subject" of it – presumably a reference to the Kreisleriana section.4

Perhaps his earliest mention in Anglophone literature was a sonnet by Scottish poet George Farquhar Graham, "To Beethoven: Edinburgh, 8th March 1813", published in The Scots Magazine in October of that year:5

Hark! from Germania's shore how wildly floats

That strain divine upon the dying gale ; --

O'er ocean's bosom swell the liquid notes,

And soar in triumph to yon crescent pale.

It changes now! and tells of woe and death,

Of deep romantic horror murmurs low ;

Now rises with majestic solemn flow,

White shadowy silence charms the wind's rude breath.

What magic hand awakes the noon of night

With such unearthly melody, that bears

The raptured soul beyond the tuneful spheres,

To stray amid high visions of delight?

Enchanter Beethoven! I feel thy power

Thrill every trembling nerve in this lone witching hour.

The publisher George Thomson sent the poem to Beethoven the following year amid negotiations over folk-song arrangements. Beethoven responded with "a thousand thanks to the writer",6,7 though since Beethoven knew no English (Thomson's letter was in French, Beethoven's reply in Italian), he wasn't in a position to judge the poem's worth.

Fictional works with Beethoven as central character started appearing just a few years after his death. Jules Janin's Le dîner de Beethoven: conte fantastique - serialised in January 1834 in the Gazette Musicale de Paris (issues 18 and 29) - may have been the first, followed six months later when J.P. Lyser's Ludwig, about the composer's early years, was serialised in the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik.10 It was reprinted in full the following year in Lyser's Kunstnovellen11, making it probably the first Beethoven fiction to appear in book form rather than as a magazine piece.

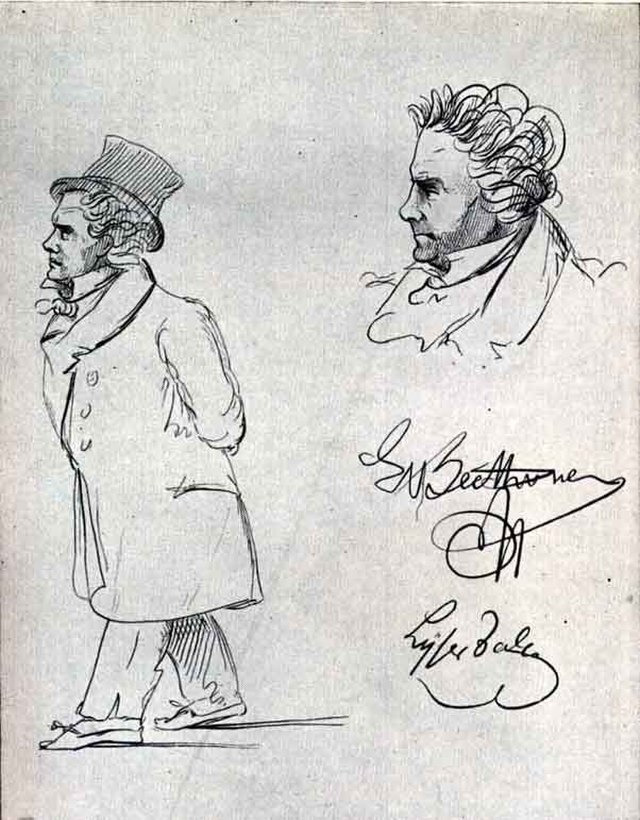

Johann Peter Lyser is best known for some drawings he made of Beethoven that are still widely reproduced, often under the mistaken assumption that they were done from life. In fact Lyser never met Beethoven or saw him in person – they were done from printed portraits and Lyser's own imagination. Lyser described himself as a "deaf painter"12, but he was also an active music critic, so presumably had some hearing, though the shared affliction may partly explain his idolisation of Beethoven. Lyser's literary hero was E.T.A. Hoffmann, whom he imitated even to the extent of borrowing titles – Kunstnovellen has a section called Kreisleriana.

The magazine Lyser contributed to, the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik, was founded and edited by Robert Schumann, some of whose articles were written as fictions. In "Florestan's Shrovetide Oration" (1835) Schumann's alter-ego described a performance of the Ninth Symphony he attended with the writer's other alter-ego, Eusebius.13

Two dramas titled Beethoven appeared in 1836. Sigismund Wiese's was a three-act play in blank verse,14 while F.-L. Berthé's15 was intended as an opera libretto. Prose fiction in the same year included Heinrich Laube's short story Beethoven und Kanne16, and Ernst Ortlepp's story sequence Beethoven: eine phantastische Charakteristik.17 A feature of some of these early fictions was a love interest named Adelaide, after Beethoven's most famous song.

Beethoven's music, rather than life, was the central theme of W.R. Griepenkerl's 1838 novel Das Musikfest, oder die Beethovener.18 In the same year an unsigned Russian story was serialised in a German periodical as Beethoven und sein letztes Quartett.19 Most notable among early writers of Beethoven fiction was Richard Wagner, whose novella Eine Pilgerfahrt zu Beethoven was first published in French translation in the Gazette Musicale de Paris in 1840, and later in English as A Pilgrimage to Beethoven.20

Perhaps the first woman writer to portray Beethoven in fiction was Elise Polko – her story collection Musikalische Märchen, Phantasien und Skizzen (1852)21 had two pieces featuring him. In one the young composer debates with his sister (he never had one) whether light or sound was the greatest gift.22 The other – similarly fanciful – tells how he found his perfect Leonore in the teenage Wilhelmine Schröder.23

Probably the first serious, full-length novel about the composer was Heribert Rau's Beethoven: historische Roman (1859), which gave biographical sources in footnotes.24 Wolfgang Müller von Königswinter's Furioso, serialised in 186025 and published in full the following year,26 had similar pretensions to accuracy in depicting Beethoven's early years.

Biographical, kultur-historische fiction was an established genre in German literature, with examples including Berthold Auerbach's Spinoza (1837) and Hermann Kurz's Schillers Heimatjahre (1843). Heribert Rau had preceded his Beethoven novel with Mozart: ein Künstlerleben (1858), and went on to write biographical novels about Alexander von Humboldt (1860), Jean Paul Richter (1861), Hölderlin (1862), Theodor Körner (1863), Shakespeare (1864) and Carl Maria von Weber (1865). Yet the genre was slow to enter English literature, where it was more usual for real-life figures to be fictionalised under different names.

Thus when it comes to the first Beethoven novel in English, a claim has to be made for Elizabeth Sheppard's Rumour (1858),27 where the temperamental, deaf German musician is called Rodomant, and locations include "Parisinia, the capital of Iris."28 Sheppard had made her name with Charles Auchester (1853), which had a character (the angelic Seraphael) modelled on Mendelssohn. The Beethoven figure in Rumour is likewise named according to his character: "rodomontade" (derived from a character in Ariosto's Orlando Furioso) means boastful talk. Before losing his hearing, Rodomant writes a song called "Adelaida", whose text paraphrases that of Beethoven's Opus 46.29 He then meets a Princess Adelaida and eventually marries her.

It seems that the first English-language novel actually about Beethoven was a translation of Müller von Königswinter's Furioso, published in 1865 with a new introduction wrongly claiming it was an authentic account based on the private writings of Beethoven's deceased friend Franz Wegeler.30 Whether responsibility for the hoax lay with Müller, the English editor Octavius Glover, or the unnamed translator, is anybody's guess; but an anonymous writer in The Saturday Review easily recognised Furioso as the Künstlerroman it truly was. The reviewer wrote: "The Germans delight in a species of fiction which bears the name of 'art-novel.' In an 'art-novel' the hero is ordinarily some celebrated painter, poet, musician, as the case may be, the leading incidents of whose life are used as a substructure, and the rest built up according to the fancy of the author, who can make his 'artist' do as many strange things and talk as many commonplaces as he finds expedient. Furioso is just one of these art-novels."31 After a thorough demolition of the book – as history, biography, music criticism or artistic literature – the reviewer concluded witheringly, "Taken cum grano - that is, read as bona fide romance - Furioso would be comparatively harmless; viewed in any other light, it is calculated to effect far more mischief than it can possibly afford amusement."32 This was prophetic as well as insightful: the scanned 1865 edition is now sold by various print-on-demand publishers with Wegeler cited as author.

Here are some belletristic works with a Beethovenian theme (or books containing one) that were published in the second half of the nineteenth century, from a list compiled by Brigitte Wesselmann and Heribert Schröder:33

Paul Scudo (1857). Le chevalier Sarti.

Hugo Müller (1868). Adelaide. Drama in 1 Akt.

Ludwig Foglar (1870). Beethoven-Legenden.

Pietro Cossa (1872). Beethoven: Dramma in cinque atti.

Hermann Josef Landau (1872). Erstes poetisches Beethoven-Album.

Gustav Adolf Nadler (1872). Beethoven in der Heimat.

Herman Schmid (1873). Beethoven. Drama.

J. Stieler (1878). Deutsche Tonmeister.

Ferdinand Hiller (1880). Künstlerleben.

Catharina F. van Rees (1882). De Koning der Symphonieën.

Wilhelm Koch (1888). Adlerflug. Novelle aus Beethovens Jugendzeit.

Leopold von Sacher-Masoch (1891). Im Reich der Töne. Musikalische Novellen.

Adolph Kohut (1892). Aus dem Zauberlande Polyhymnia.

Clara Gerhard (1894). Im Banne der Musik. Erzählungen fur die müsikalische Jugend.

Oskar Höcker (1894). Lorbeerkranz und Dornenkrone. Eine Erzählung aus Beethovens Tagen.

Adolf von Wilbrandt (1895). Beethoven.

In the twentieth century the number exploded, and in the twenty-first shown no sign of slowing. The earliest film, according to an article by Jürgen Pfeiffer, was a now-lost French silent film called Beethoven, mentioned in the press in January 1913.34 Pfeiffer found a further six silent films up to 1927, when the German biopic Beethoven was released to coincide with the first centenary of the composer's birth.35 How many films and novels will there have been by the time the second centenary comes round?

In Beethoven's Assassins, a present-day character wonders whether to write a novel about Beethoven, and decides otherwise. "Were it not that the plethora of pre-existing attempts already gave sufficient argument against, others could easily be adduced. The true subject is greater than any possible imitation. Should the intention be immanent critique rather than didactic discourse, there would have to be a mutual inter-relation of form and content, in a manner I can’t imagine. Anyway, I don’t know how to write a novel."36

Addendum. I was not aware while writing my novel of a delightful piece by Berlioz, published in the Journal des débats in 186037 and translated as "Beethoven in the Ring of Saturn (The Mediums)".38 Had I known of it, I would doubtless have mentioned it somewhere in my story, since it connects so well with the novel's theme of spiritualism. Berlioz's short, witty piece imagines a medium summoning the spirit of Beethoven, who resides in the rings of Saturn. The deceased composer dictates a sonata that is played and found to be "a fine full-blown piece of nonsense" (une platitude complète, un non-sens, une stupidité). It is evidence of Beethoven's "fourth period" (quatrième manière), unintelligible to earthlings and proof that beauty is relative, not absolute, so that among current productions lauded on Earth, many "will be hissed off the stage in Saturn, Jupiter, Mars, Venus, Pallas, Sirius, Neptune, the great and little Bears, and the Wagon constellation; being in short, nothing but infinite platitudes for the infinite universe."39

References

1. Schindler-MacArdle, p39

2. Schindler-MacArdle, p81 n12

3. Schindler-MacArdle, p80 n9

4. Conversation Books Vol 1, p326

5. Scots Magazine, Vol 5, p776, October 1813

6. Anderson II, p468 (Sep 15, 1814)

7. Thayer-Krehbiel II, p290

8. GMP 1, p1

9. GMP 2, p1

10. NZfM 1, p121

11. Lyser, p123

12. Benjamin, title page

13. Schumann, p31

14. Wiese, p193

15. Berthé

16. Laube, p148

17. Ortlepp

18. Griepenkerl

19. BKLA, p241

20. Wagner

21. Polko

22. Polko-Maudsley p88

23. Polko-Maudsley, p90

24. Rau

25. Breuning, p30

26. Königswinter, p103

27. Sheppard I

28. Sheppard II, p62

29. Sheppard I, pp243-4

30. Müller

31. SRPLSA, No. 482, Vol. 19, January 21 1865, p90

32. SRPLSA, No. 483, Vol. 19, January 28 1865, p122

33. Nachwelt, pp95-114

34. Nachwelt, pp224

35. Nachwelt, pp225

36. Crumey, p450

37. JDD 60, p2

38. Berlioz (Critical Study), p159

39. Berlioz (Critical Study), p165