Some things I dug up while researching my novel Beethoven's Assassins.

Beethoven in Fiction

When was Beethoven born?

What caused his deafness?

Who was the “Immortal Beloved”?

Why "Moonlight" Sonata?

Was Beethoven a Freemason?

What was the "Incident at Teplitz"?

Why "Hammerklavier" Sonata?

Who first played the Hammerklavier Sonata?

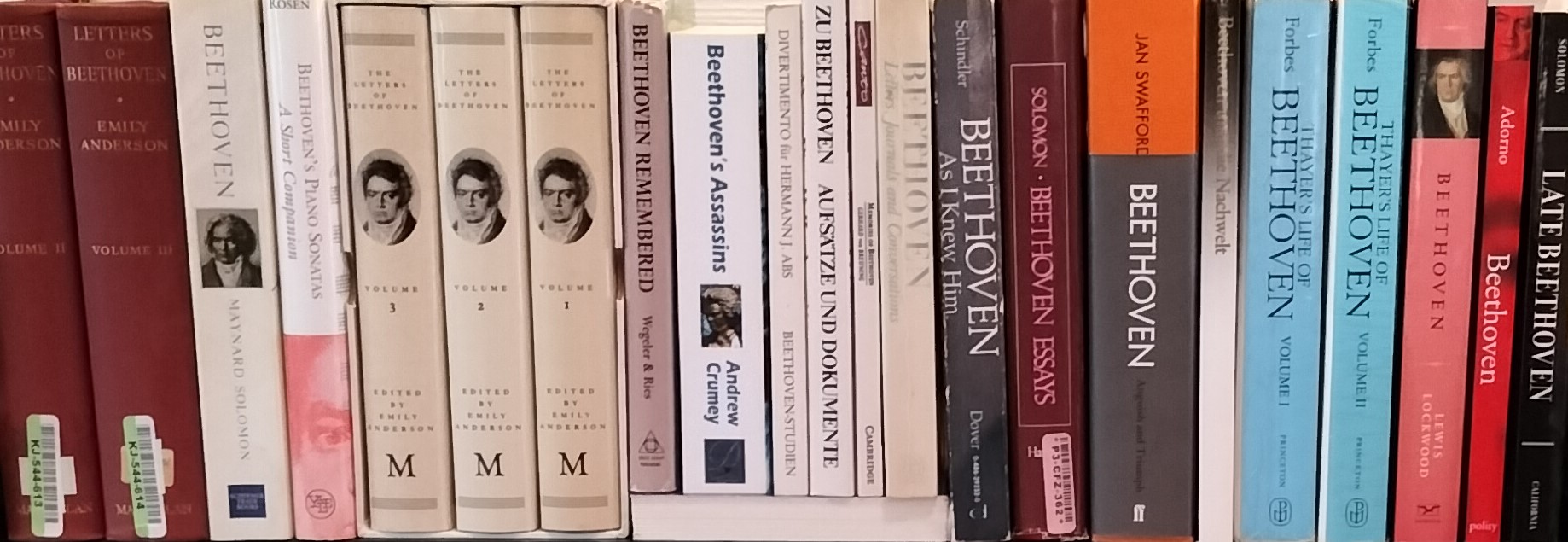

Bibliography

Why is Opus 27 Number 2 known as the "Moonlight" Sonata?

The German nickname Mondschein-Sonate was firmly established by 1840, when Anton Schindler's biography of Beethoven first appeared. A British edition by Ignaz Moscheles came out in the following year, and is probably where the nickname first appeared in English – though not quite as we now know it. Writing under the false supposition that the sonata's dedicatee, Countess Giulietta Guicciardi, was Beethoven’s "Immortal Beloved", Schindler added a footnote that Moscheles translated thus:1

"This sonata, quasi Fantasia, Op. 27, is known in Austria by the inappropriate appellation of 'Moonshine Sonata,' which is meant to designate nothing more than that enthusiastic period of Beethoven’s passion. "

The sonata was known as both "moonshine" and "moonlight" throughout the 19th century, the former falling from favour when "moonshine" came to be associated with illicit alcohol. A tongue-in-cheek columnist in the May 1922 edition of Practical Druggist magazine wrote, "If Beethoven would have had a presentiment that moonshine could ever get into such bad repute, he surely would not have named his wonderful sonata in C Minor [sic], 'Moonshine.' Who would at that time have believed that he would be going to the dogs in the year of our Lord 1922?"2

The standard, much repeated story of the nickname's origin comes from Wilhelm Lenz's Beethoven et ses trois styles, published in 1852. Lenz wrote:3

Rellstab compare cette œuvre à une barque, visitant, par le clair de lune, les sites sauvages du lac des quatre cantons en Suisse. Le sobriquet de 'Mondscheinsonate', qui, il y a vingt ans, faisait crier au connaisseur en Allemagne, n'a pas d'autre origine. (Rellstab compares this work to a boat, visiting, by moonlight, the remote parts of Lake Lucerne in Switzerland. The soubriquet Mondscheinsonate, which twenty years ago made connoisseurs cry out in Germany, has no other origin.)

Lenz didn't specify where exactly Ludwig Rellstab made the comparison, but if "twenty years" were taken literally, it would suggest a date of 1832. Thus it came to be assumed that the nickname started five years after Beethoven's death, in something Rellstab wrote at that time – though nobody could identify an actual source.

With the arrival of the world wide web, Rellstab's complete writings could easily be scoured, leading to the discovery that his moonlight comparison was actually made during Beethoven's lifetime. It's even possible that Beethoven could have been aware of it.

Ludwig Rellstab was a contributor to the Berliner allgemeine musikalische Zeitung (BAM), a weekly music magazine founded in 1824 under the editorship of Adolf Bernhard Marx, and published by Adolph Martin Schlesinger. All three men were well disposed towards Beethoven; Schlesinger had published some of his music (e.g. the piano sonatas Opp. 109-111, favourably reviewed in the magazine), and Marx would later write a biography of the composer. Rellstab's story Theodor: eine musikalische Skizze, serialised in the magazine in the summer of 1824, features musicians who admire Beethoven's works. One of them imagines the adagio of the C-sharp minor sonata as follows:4

Der See ruht in dämmerndem Mondenschimmer; dumpf stößt die Welle an das dunkle Ufer; düstere Waldberge steigen auf und schließen die heilige Gegend von der Welt ab; Schwäne ziehen mit flüsterndem Rauschen wie Geister durch die Fluth und eine Äolsharfe tönt Klagen sehnsüchtiger einsamer Liebe geheimnisvoll von jener Ruine herab. (The lake reposes in twilit moon-shimmer, muffled waves strike the dark shore; gloomy wooded mountains rise and close off the holy place from the world; ghostly swans glide with whispering rustles on the tide, and an Aeolian harp sends down mysterious tones of lovelorn yearning from the ruins.)

This must have been what Lenz had in mind; though the boat on Lake Lucerne – which became as definitive as the fictitious date of 1832 – was presumably a product of Lenz’s imperfect memory or fertile imagination.

Did Beethoven read Rellstab's story? I don't know – but he had every reason to follow the magazine, given its coverage of his music. He even met Rellstab, who came from Berlin for a two-month stay in Vienna in the spring of 1825. They had several meetings, despite Beethoven's poor health, and discussed possible opera projects – Rellstab having to write his remarks. Recalling events many years later in a memoir, Rellstab described Beethoven's eagerness to show off the fine tone of his Broadwood piano, on which he casually struck a chord without looking at his hands. "Never again will one penetrate my soul with such a wealth of woe, with so heart-rending an accent! He had struck the C major chord with his right hand, and played a B to it in the bass, his eyes never leaving mine; and, in order that it might make the soft tone of the instrument sound at its best, he repeated the false chord several times and — the greatest musician on earth did not hear its dissonance!"5 Was any mention made during these meetings of Theodor, or the C-sharp minor sonata? Rellstab doesn’t say.

Rellstab's image was Mondenschimmer rather than Mondenschein, so when did the latter start to catch on as a nickname? The earliest printed reference I can find is Ernst Ortlepp's 1836 book, Beethoven: eine phantastische Charakteristik, which has the further distinction of being one of the earliest appearances of Beethoven as a fictional character. The book consists of three stories, one of which – Beethovens erste Liebe – opens with a soiree where Beethoven's music is heavily criticised by experts, and defended by the young heroine, Adelaide.6

Aber die Mondscheinsonate dieses von Euch so schlechthin verdammten Genies ist denn doch ein Werk, das mir wie etwas völlig Neues vorkommt. In allen Sachen von Haydn und Mozart finde ich nichts Ähnliches! (But the Mondscheinsonate by this genius you so utterly condemn is a work that strikes me as something completely new. In all things by Haydn and Mozart I find nothing similar!)

Adelaide later meets Beethoven, who falls in love with her, but she marries someone else. Guess what song Beethoven supposedly composes afterwards in tribute.

An item in a Vienna music magazine, the Allgemeine Musikalischer Anzeiger, dated 16th March 1837, said the sonata "expresses the romantic glow of a mild summer night, which is why it has not entirely unjustly been called the Mondscheinsonate".7 No sign there of any lake – the mood that people typically got from the sonata's opening adagio was of love and yearning, an association that was certainly present during Beethoven's lifetime. In the BAM of 10th March 1824, Adolph Marx called the adagio "this holy lament of unhappy love"8 and compared it with the arioso dolente of Opus 110, his image for that latter piece being a painting by Correggio of Mary Magdalene.

Apart from the Lake Lucerne story, Lenz's Beethoven et son trois styles is the locus classicus for another factoid concerning Opus 27 No. 2; the assertion that its original nickname in Vienna was "Arbor Sonata" (Laubensonate).9 Lenz repeated this in Beethoven: eine Kunst-Studie (1860), saying it was because Beethoven was imagined to have "improvised the adagio in a garden pergola for the beautiful countess".10 I haven't been able to find any reference to Laubensonate prior to Lenz.

Rellstab died in 1860, by which time the "moonlight" nickname was known everywhere, as was the claim that he started it. So what did Rellstab have to say about it? In his memoir, completed not long before he died, he had much to say about his long career, but nothing at all about the one thing most people nowadays remember him for. I haven't been able to find any direct comment from him about the nickname; the closest I've found is in his review of a performance of the sonata by Franz Liszt, given in Berlin on 1st January 1842. Rellstab wrote:11

"In general, it has always been felt that the C-sharp minor sonata has a nocturnal colouring, resembling a gloomy magical landscape in moon-shimmer [Mondenschimmer]. The ardent nature of our performing artist [Liszt] cannot be satisfied with this generally romantic coloring. He still throws in dark cloud shadows, faintly shining shimmers of lightning, distant rolling thunder, sudden storm blasts that chase up the waves in the deepest depths... We confess that we agree with the opinion of a great, deceased artist [Ludwig Berger], who considered the scherzo of this sonata, which does not match the great style of the first and last movements, to be a strange section. How poetically Liszt is able to solve and supplement such difficulties through his interpretation, is shown by his witty reply to a remark made to him about this movement in the foregoing regard. It seemed to hit home, but he found a quick and most happy way out: "Ah, c'est un fleur entre deux abymes!" A remark that needs no translation. In this way he showed us the dark blood in the moonlight."

Rather than lay claim to the nickname, Rellstab seems to have distanced himself from it, referring to the nocturnal association as a general opinion. Might it already have been in circulation when he wrote Theodor two decades previously? Or had he just come to realise the danger of images that can limit rather than broaden our appreciation? In the review he also said:12

"This sonata as a whole is of such exciting power that each individual is affected differently by it; we have heard it from many very distinguished artists, and each gave us something different... Beethoven is a sphinx, whose wonderful riddle everyone interprets differently; we approach the truth without fully grasping it; in the end, every work created from the unfathomable depths of genius remains a higher equation that can only be solved by a method of approximation."

References

1. Schindler-Moscheles, p54

2. Bodemann, p28

3. Lenz, p225

4. BAM, p274

5. Sonneck, pp188-9

6. Ortlepp, p8

7. AMA, p41

8. BAM, p88

9. Lenz, p221

10. Lenz 2, p79

11. Rellstab, pp6-7

12. Rellstab, p6