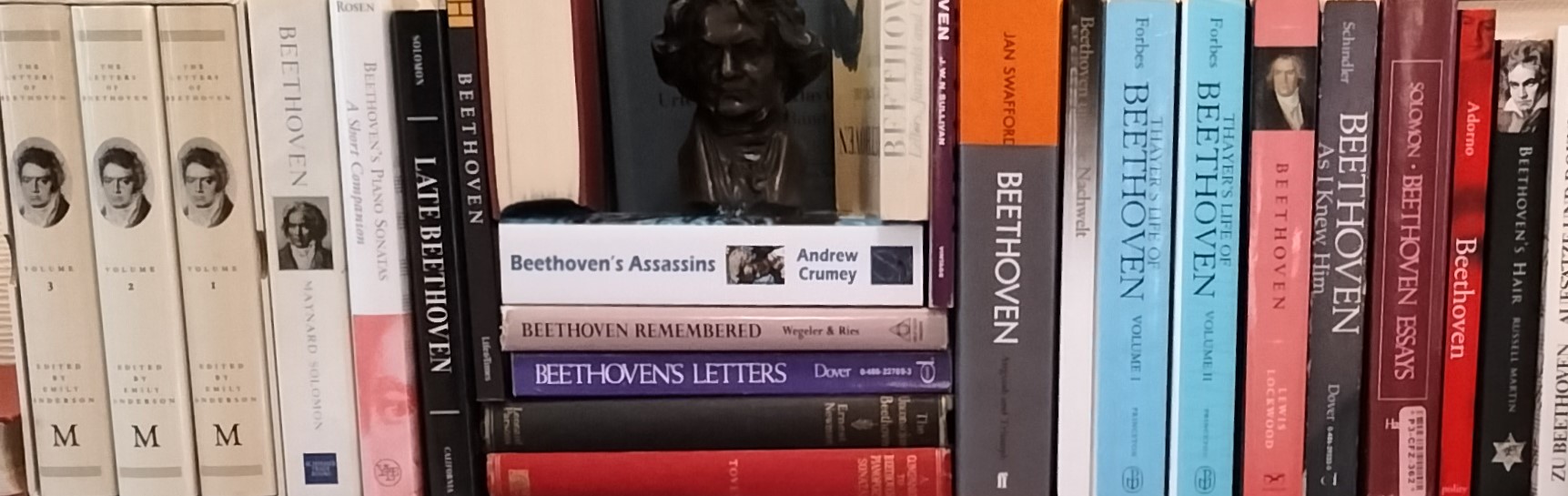

Some things I dug up while researching my novel Beethoven's Assassins.

Beethoven in Fiction

When was Beethoven born?

What caused his deafness?

Who was the “Immortal Beloved”?

Why "Moonlight" Sonata?

Was Beethoven a Freemason?

What was the "Incident at Teplitz"?

Why "Hammerklavier" Sonata?

Who first played the Hammerklavier Sonata?

Bibliography

Simple answer – no one knows, and we probably never will. When Beethoven died, a three-part love letter written by him at an unknown date was found among his papers, intended for an unnamed recipient referred to in the letter as unsterbliche Geliebte – “immortal beloved”.1 Beethoven’s sometime friend and early biographer, Anton Schindler, guessed the woman to be the dedicatee of the Moonlight Sonata, Countess Giulietta Guicciardi.2 Subsequent research showed this was impossible; place names and other details in the letter have enabled scholars to prove it must have been written on 6th or 7th July 1812 while Beethoven was staying at the spa town of Teplitz (now Teplice, Czech Republic),3 and the intended recipient must have been someone who planned to be in Karlsbad (now Karlovy Vary, Czech Republic).4 That isn’t enough to identify her with certainty: as Maynard Solomon observed, the woman might have been someone “wholly unknown to Beethoven researchers”.5 She certainly wasn’t “Elise”, the unknown dedicatee of the little piano piece that Beethoven didn’t consider worthy of publishing, but which became one of his best known works when it was discovered after his death. The autograph score was in the possession of Therese Malfatti, niece of Beethoven’s doctor, Johann Malfatti, and though there’s circumstantial evidence that Beethoven fancied the teenage Therese as a potential wife,6 she can be ruled out as Immortal Beloved. She probably wasn’t Elise either, unless the name on the score (now lost) was a misreading of Beethoven’s handwriting.7

Incidentally, Dr Malfatti is rather more interesting, to me at least, than his niece. He was part of an intellectual circle that included physician Ignaz Troxler – founder of “biosophy” – and artist Ludwig Schnorr, who drew Beethoven’s portrait in 1810. Another of Malfatti’s friends was Friedrich Schlegel, who proposed India as the place from which civilisation was brought to Europe by an “Aryan tribe” (arischen Stamm).8 That might explain how Malfatti later came to believe in “the mystic organon of mathesis”,9 a supposed Brahman wisdom based on numbers and hieroglyphs, and why Beethoven copied extracts from Indian literature into his commonplace book.10 Malfatti was also drawn to Franz Mesmer’s theory of animal magnetism, and was invited to Prussia to see research being done there.11 Austria was less tolerant of mesmerism than Prussia, so Malfatti and his circle had to exercise caution. When the painter Schnorr began practising as a healer after attending sessions with Schlegel, he operated in semi-secrecy while continuing to work as an artist. In 1825, trying to cure a woman of nervous coughing, Schnorr asked a friend to play soothing piano music. The piece was Schubert’s German Dance, Opus 33 number 7, and the pianist was Schubert himself.12 Beethoven would presumably have known such seances took place, and would certainly have been aware of the curative claims of Magnetiseurs. Is it conceivable that he was never at least offered such treatment? In 1817 Beethoven wrote to a friend complaining about a “wily” (pfiffig) Italian doctor whom he suspected of “secondary motives”.13 He probably meant Malfatti’s assistant, Bertolini, who claimed long after Beethoven’s death to have been intermediary in an abortive music commission.14 Bertolini also said he’d destroyed all his documents relating to Beethoven, which some have taken as sufficient evidence that he treated the composer for syphilis.15 It’s equally strong evidence that the treatment was mesmerism; in other words, no evidence at all.

Returning to the Immortal Beloved letter, we have to wonder why it remained in Beethoven’s possession. Was it a draft, or returned by the recipient, or never sent? Beethoven kept the letter in a hidden compartment of his desk, along with some other precious items. Was he trying to make sure that no one would ever see it? Actually the reverse – the compartment was where he also kept bank share certificates that were meant as inheritance for his nephew Karl. It was a frantic search for those shares that led to the letter being discovered. Beethoven wanted the world to see it – and didn’t want us to know who the woman was. Did she even exist? The sad truth about Beethoven’s love affairs is that they were mostly inside his head.

The closest, most sustained relationships in Beethoven’s life were with men. The ones searching his apartment for share certificates after his death were Stephan von Breuning, Anton Schindler, and Beethoven’s brother Johann. None of them were aware of the compartment, and were stumped until the arrival of the one person who did know of it – Karl Holz.16 Nearly thirty years Beethoven’s junior, he was the last in a series of close friendships the composer had with younger men. Anton Schindler (25 years Beethoven’s junior) had filled the same role for a while, and before him there was Franz Oliva, a bank employee and capable linguist sixteen years younger than Beethoven.17

How Beethoven and Oliva first met isn’t clear, but it would have been around the time when the 39 year-old composer was working on the Emperor Concerto. Soon after, Beethoven dedicated a set of piano variations to Oliva (Opus 76) – its theme was to become one of Beethoven’s best-known tunes, remodelled as a Turkish march for The Ruins of Athens. When Beethoven was suffering from bad headaches in 1811, Dr Malfatti recommended the spa waters at Teplitz. Beethoven took Oliva there with him.18 They quarelled, and Oliva left two days before Beethoven,19 but the following year they discussed going to England together.20Again they fell out, more seriously, and Beethoven went alone to Teplitz, where his letter to the Immortal Beloved has attracted infinitely more attention than whatever went on with Oliva. Most tantalising is the thought that the Piano Sonata Opus 81a – “Farewell, Absence, Return”, dedicated to Beethoven’s paymaster Archduke Rudolph, was written at a time when Oliva meant far more to him personally.

According to Schindler’s biography, Oliva emigrated to Russia in 1817, never to return.21 Schindler must have known this was untrue – Oliva came back from there in 181922 and quickly re-established himself as Beethoven’s closest companion, as the conversation books make clear. The ones for 1820 are replete with monetary calculations, mostly by Oliva who had better numeracy than Beethoven. We see them shopping together – Oliva writes that a hat they’re looking at costs 16 florins, then at the market informs Beethoven white pepper is healthier than black.23 In March 1820, Beethoven sat for a now-famous portrait by Joseph Stieler showing him holding the manuscript of the Missa Solemnis, pencil in hand. Oliva thought the finished portrait a fine likeness;24 it was commissioned by Beethoven’s friends, Franz and Antonie Brentano – the latter nowadays seen as a leading Immortal Beloved contender.25

In April 1820 we find Beethoven making plans to spend the summer at Mödling, a few miles south of Vienna. Oliva saw to the arrangements, and in the midst of a conversation about transport and bedding (cotton sheets 10 florins, silk 18 florins), he asked Beethoven about a “new little piece” that could perhaps go in a sonata for the publisher Schlesinger.26 It became the first movement of Opus 109. Beethoven took spa treatment at Mödling and worked on the Missa Solemnis. He also made regular trips back to Vienna, seeing Oliva there and sometimes remaining in the city overnight, at places arranged by Oliva. (Conversation Book 15, Leaf 13v, entry by Oliva: “You must close up the room and take the key down to the 1st floor. I’ll take care of everything for you. Good night.”)27 On at least one occasion, Beethoven seems to have stayed overnight at Oliva’s apartment. (Conversation Book 16, Leaf 26r, entry by Oliva: “Where are you going? Don’t you want to have breakfast?”)28

Though there’s no clear evidence either way, I personally doubt that there was any kind of physical relationship between Beethoven and Oliva. There must however have been a close emotional bond, and there was definitely a practical one. Oliva played the sort of domestic role that a wife might have, looking after the older man’s everyday needs and taking a deep interest in every aspect of his life – from publishing deals to mousetraps.

Beethoven finished Opus 109 in September 1820,29 then a few weeks later enquired – on behalf of a “friend” – about a house and vineyard for sale in Mödling.30 Who the friend was, or whether he even existed, is unknown – the conversation book for the period ends too soon, with a falsified entry by Schindler,31 and the next book to have survived dates from over a year and a half later. At the end of 1820, Oliva went back to Russia for ever, leaving a gap for Schindler to move into.32

Schindler and Holz filled a similar domestic role to Oliva, but for shorter periods. Maynard Solomon speculated that Schindler was homosexual,33 and Beethoven joked that the word Holz (German for wood) was of neutral gender,34 but again there’s no reason to suppose that Beethoven was physically attracted to either man. Neither, I suspect, meant as much to Beethoven as Franz Oliva had – the only one of the three who received a musical dedication. In 1854 a Beethoven scholar went looking for Oliva in Saint Petersburg and was told he’d died from cholera six years earlier. All his correspondence had been destroyed in a fire.35

Who was the biggest love in Beethoven’s life? Maybe it was Franz Oliva.

1. Thayer-Forbes, pp533-535Who was the “Immortal Beloved”?

References

2. Schindler-MacArdle, pp104-110

3. Solomon, p217

4. Solomon, p219

5. Solomon, p219

6. Thayer-Forbes, p486

7. Thayer-Forbes, p502

8. Schlegel, p459

9. Malfatti, p1

10. Solomon 3, pp265-269

11. Oppert, p19

12. Feuerzeig, p232

13. Anderson, p683

14. Thayer-Forbes, p648

15. Palferman, p668

16. Thayer-Forbes, p1052

17. Thayer-Forbes, p462

18. Thayer-Forbes, p511

19. Thayer-Forbes, p516

20. Thayer-Forbes, p532

21. Schindler-MacArdle, p202

22. Schindler-MacArdle, p338 n135

23. Conversation Books, Vol 2, p145

24. Conversation Books, Vol 2, p181

25. Solomon, p231

26. Conversation Books, Vol 2, p170

27. Conversation Books, Vol 2, p274

28. Conversation Books, Vol 2, p317

29. Anderson, p902

30. Anderson, p903

31. Conversation Books, Vol 2, p347

32. Thayer-Forbes, p772

33. Solomon 3, p150

34. Anderson, p1243

35. Thayer-Forbes, p462